Reverie Nature Podcast

Delve into a diverse array of topics, including wilderness survival skills, bushcraft, nature soundscapes, captivating stories of environmental heroes, secrets in animal tracks, and much more. Ideal for outdoor enthusiasts seeking to enhance their skills or seasoned guides collecting little gems of insight.

Donation or subscription: Buy me a coffee

Hosted in the heart of a land trust site and hiking trailhead: Blueberry Mountain (cliffLAND)

Reverie Nature Podcast

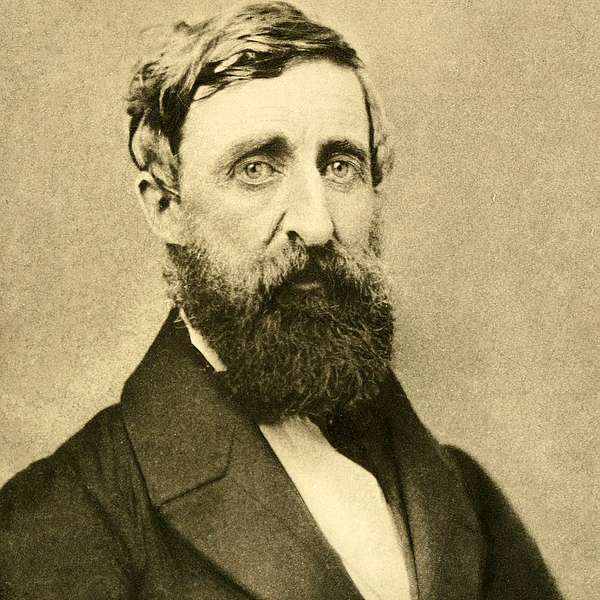

Finding Solitude in Nature: A Journey with Henry David Thoreau

Please support the podcast through a donation or subscription at

Buy me a coffee

We venture into the serene landscapes of transcendentalism, conservation, environmentalism, and activism. Thoreau is an iconic figure whose contemplative writings continue to resonate with nature lovers and seekers of inner peace alike.

In his seminal work, "Walden; or, Life in the Woods," Thoreau invited us to accompany him to the shores of Walden Pond, where he spent two years living deliberately, simplifying his existence, and communing with nature.

Thoreau had a quest for simplicity, a reverence for the rhythms of the natural world, and an enduring belief that "the universe is wider than our views of it.

So now, Place yourself at Walden Pond, sitting by a small cabin, with the wind rustling the leaves under a Sienna-tinted sunset, and listen to storyteller Howard Clifford do his reenactment of Henry David Thoreau.

Flute music and soundscapes by Chad Clifford

Please consider leaving a rating and/or review wherever you listen to the podcast. Don't forget to share a good episode on social media too. The mid-roll ad on this podcast includes the song entitled House of Mirrors, by Chad Clifford (Pete Meyer on flute).

Thank you for tuning in to the Reverie Nature Podcast! Your support keeps our adventures alive. Be certain to subscribe for more captivating episodes exploring the wonders of the natural world. Join us on this journey to embrace nature's song and preserve the beauty of our planet. Together, we can make a difference.

Chad Clifford

Please support the podcast through a donation or subscription at:

Buy me a coffee

Let’s again, Embark on a captivating journey through time as we breathe life into the stories of visionary figures who shaped the course of environmental conservation: John Muir, David Thoreau, and Grey Owl, with more . From the rugged Sierra Nevada Mountains to the tranquil shores of Walden Pond and the untamed forests of Canada, these reenactments will transport you to the heart of their most defining moments. Let their stories inspire and ignite your passion for nature and environmental stewardship. The third episode in this series is called Finding Solitude in Nature: A Journey with Henry David Thoreau: we venture into the serene landscapes of transcendentalism. Thoreau is an iconic figure whose contemplative writings continue to resonate with nature lovers and seekers of inner peace alike.

In his seminal work, "Walden; or, Life in the Woods," Thoreau invited us to accompany him to the shores of Walden Pond, where he spent two years living deliberately, simplifying his existence, and communing with nature.

Thoreau had a quest for simplicity, a reverence for the rhythms of the natural world, and an enduring belief that "the universe is wider than our views of it.

So now, Place yourself at Walden Pond, sitting by a small cabin, with the wind rustling the leaves under a Sienna tinted sunset listen to story teller Howard Clifford do his reenactment of Henry David Thoreau.

Transcribed by TurboScribe.ai.

My name is Henry David Thoreau. I was born 1817 in Concord, Massachusetts, a small town about 20 miles west of Boston.

I was a third sibling. I had one brother that was older, one sister that was older, and one sister that was younger. My father operated a pencil factory.

It brought in reasonable income. We were considered neither poor nor wealthy. My childhood was fairly normal.

I was subject to some fainting spells, but it was not true. But my older brother, I became extremely close to him. He was two years older, and I don't ever even recall having the typical fight that takes place between siblings.

But we were the exact opposite. He was very outgoing, fun-loving, and very popular. Well, I was more reserved, a bitch, have a loner.

But somehow, we bonded more than brothers. We were deep, best friends. My common friends that we had in common said I was so serious that some said I was sober like a judge.

And therefore, I did get the nickname. It wasn't malicious. It was just describing who I was.

They called me judge. I do recall one experience from my early childhood. It was told by my mother to her friends from time to time.

I was in the bedroom with my brother John. And mother was up in the middle of the night for something, and she checked in to see that we're okay. And she was surprised I was wide awake, looking out the window.

And she said, Henry, why are you awake at this time and night? And I said, well, I'm looking at the stars. I want to see if I could see God behind them. Well, of course, this was an amusing story to my parents, the innocence, the naivety of children, how they see things.

But as I think about it, perhaps that was just an indication of how my personality was forming, how I was becoming, who I was to become. Because I was always considered, and I considered myself to be independent, to be a free spirit. Some thought I was rebellious against social conventions, but I didn't consider myself rebellious.

I just thought, if anyone was to tell me the term authority, someone outside myself, what I was to believe and how I was to act, then wasn't that taken away from my own freedom, from my own liberty, even from my own being a person. It wasn't that I didn't accept that many of these conventions were true, I just felt you shouldn't accept them unquestionably, which most people seem to do. And this became more evident as I grew older.

In 1833, our family, as I said, was not wealthy. They certainly didn't have enough financial means to send all children to university. They felt they could only afford to send one, and even that took sacrifice.

Ordinarily, it would be my brother John, he was the oldest, but he was more outward going, fun loving. Why was the serious type loved books? And so the family chose that I should be the one that would probably be the most fitting to send to Harvard. I was a good student, but as I mentioned, I was an independent thinking thinker too, and sometimes I found myself maybe as an adolescent rebelling a bit.

For example, to go to chapel, the rule was you need to have a black coat. I chose a green coat. I guess just to indicate my independence from rules.

Probably the two greatest authorities that the university taught, at least in the courses I took, was the first was Darwin, and he was sort of like me. His writings challenged all the social conventions and beliefs of the day, but as I read them, it just seemed to ring true. It seemed to fit with my own experiences, but the other authority that the university pushed was Adam Smith, the wealth of nations.

Now, if you accepted his assumptions, it was pretty hard to argue. It was circular in some sense. If his assumptions was true, then everything else he said made sense, and certainly most people accepted that he was the most important figure for the economics of our nation.

But somehow, it just didn't seem right to me. I couldn't quite put my finger on it, but I just somehow knew that he was not for me. Because I graduated at 75% of the university, I was given the opportunity to speak.

So it was Adam Smith that sort of drove some of my thoughts. I remember making this statement, the commercial spirit of this day rests in the love of wealth that makes people selfish and greedy. Wouldn't it be better if the for the world would be a better place if people made riches the means and not the end of existence.

Another factor at the university that really influenced me didn't come for my courses. It came from their wonderful library. I came across that great philosopher Emerson, his book, Nature.

And as I read his book, it just seemed to me to be everything I was looking for. And when I graduated, four years later, 1837, I learned that Emerson had actually come to take residence in Concord. I couldn't believe this famous man in my small town.

And while I was home, I learned that he was going to be speaking at Boston at Harvard. And so I walked the 20 miles there and 20 miles home just to be able to hear him speak. And it so happened that a person that knew Emerson mentioned to him that there was a new graduate from Harvard that lived in his same town and that he had walked this 20 miles just to hear him speak.

Were this tweaked Emerson's interest? I couldn't believe it. In October, I was invited by him to come to his home for a visit. Now, I must say, almost everybody that meets Emerson, he just automatically seems to command respect and even from his family members.

But he had this other trait. He was able to put you completely at ease. I recall he didn't really talk much about himself.

He was only wanting to get to know me, asking me questions about myself. Deep probing questions as if I was important to him. It was one question that he asked me that actually changed my life.

He said, young man, where is your journal? And I had to admit, I didn't own such a thing. And he said, if I can give you any advice at all, the most important advice I can give you is to get a journal and take it with you everywhere you go. Because you'll never know when your mind will come across some truth.

Or your mind will trigger something, a new thought. And if you don't write it down, you will lose it. It's the most important thing that you can do.

And so that same day, I went out and bought a journal and made my first entry. As I look back over my life now, 25 years later, I had 14 volumes and over 2 million words, it was in truth the best advice a young man could receive. I got a job actually being the schoolmaster for the very school that I had attended.

I taught there for about two weeks when the school inspector came to evaluate my work. He spent a few days not saying anything, just observing. And then he said to me, it looks like your students are doing well.

And they seemed to like you. And I said, well, I like them too. And he said, but I noticed, you've never once done my time here, ever whipped any of them.

And I said, well, there's never been a need to. And he said, oh, no, that will never do unless they fear you. It's not that they should like you.

They've got to fear you. Or else they will never, never learn when things, when learning gets tough. I couldn't believe that he was serious though I know that most people felt like he did, that unless there was punishment or a stick, you wouldn't put out the effort to learn.

But I knew that the best way to learn is because you're curious. You want to find out things for yourself. And that in itself is motivation enough, more important than just being fearful of the school teacher.

But he wouldn't listen to anything I had to say. It was just like he had accepted everything he had been taught. And it was just so obvious to him that this was true, but there wouldn't any room to think outside of what he had received.

And I became angry. I shouldn't have, but I did. But it was just to me, sits in the front to have accepted the social convention without even willing to look at other possibilities.

And so I quickly grabbed a tall student, and that was near me, actually taller than I was, and began to whip him. Well, that student looked at me with a surprise in his face. The rest of the class stopped what they were doing, and they had never seen me act this way before.

And then I turned to the school inspector and said, I resign. Well, of course, my parents were upset. I mean, they had sacrificed for me to go to university, and here I got what they considered a good job.

And I had in two weeks acted like this. Well, I turned to my brother John, who I mentioned, became my, was always my best friend, and asked him if he would assist me in starting a private school. And so in 1838 to 1841 we ran a private school.

And it went very well. The locals were always surprised to see us with the students visiting the various shops, wondering through the woods, being outdoors as much as possible, because this is where I thought learning really took place. One of the students that I'll never forget was the Louisa May Alcott.

See, went on to write Little Women. It's a classic today. But my brother had sickness spells, and he came down with, I can only assume, with tuberculosis.

And so we had to cancel the school. But it was at that same time I was invited by Emerson to live with him in his household to be a tutor to his children, and to look and to manage household affairs while he was away on many of his trips. That went well.

But then the saddest thing that ever happened in my life took place. It was January 11th, 1842. My brother John had been shaving.

He nicked himself, and he soon developed lock jaw. A terrible disease. I recall holding him in my arms as he passed away.

This made a big change in my life, the way I looked at life. And within, oh, by early 1845, I decided I need to turn to something else. I need to really discover what life is really.

What's the meaning of life? And I went to Mr. Emerson, because he owned 50 acres, I believe it was, at Walden Pond. And I asked him if he would let me build a small cabin there, and live for, I don't know how long I want to live there, but I just wanted to discover myself, discover the meaning of life, and that I would, when I left, would leave the cabin to him. He agreed.

And so on March 5, 1845, I began to build with my own hands, with all the scrap lumber I could find, a little cabin, 15 by 10. And I moved in on in July the 4th. I wrote, I went to front only the essential facts of life, and see what I could learn, what it had to teach, and not when I come to die, discover that I had not lived at all.

Now many people were saying, well, why are you going to do that? It's unhealthy to live alone. And I remember wondering that myself. Would it be healthy to live alone like that? But I have to tell you, it's not going out into the wild tracks of wilderness, but I would be really completely alone.

I mean, it was only 20 minute walk to town, which I did about once a week to get my clothes washed. And also, some of the visitors would come to the cabin from town just to see what I was up to and to have a chat. And I always welcomed them.

But there's a big difference, a complete difference between the Walden Pond, that 60 acre beautiful lake, and town. In town, the first thing I saw when I got up was another human being. Look out the windows and there was roads, there was stores, there was school.

I mean, everything I looked with dominated by man, nature was subdued, played only a background picture in life. But at Walden Pond, it was different. There was no sign that there was dominated by humans.

It was nature being self-willed, doing what it would do when it wasn't under the thumb of man. And all being healthy, I found it the healthiest thing I could imagine. I named myself the inspector of storms.

If it was a snowstorm, I went out. I measured the snow, looked at the differences that's seen in snow, then in summer. If it was a thunderstorm, if it was a rainstorm, a hail storm, I was out there looking to see how that affected everything.

I actually spent hours observing duck eggs to actually watch to see what took place as they hatched. I also watched frogs tadpoles. I once told Emerson, I believed frogs were the birds of night.

Emerson once told somebody that he saw me standing up to my waist almost like in a trance. For hours on end in a swamp. Well, I recorded when the buds came out, when the leaves unfolded.

I remember spending hours under a tree in a storm with a microscope, spending the whole day just looking at the crevices and the bark, discovering insects, fungus, all the life that was there. The locals had said that this pond was bottomless, that it had no bottom. It was just bottomless.

Well, I couldn't believe that. But I got out in a boat, had a fishing line and a stone, and I discovered that it was in fact 102 feet deep. I also found that walking at night, my feet were better than my eyes to find my way around.

The instruments I took here and there and everywhere, they were often used even today by scientists. It was the most wonderful two years, two months, and two days of life. I just, before I leave Wallen, I just want to share one other experience about the power of sitting in a boat on this beautiful pond, fishing, but playing a flute.

The flute seems to be so magical. It just fit in and it reminded me that silence is what you hear inwardly. Noise is what you hear from external sources.

And I would become so entranced, so measureized by displaying the flute and taking in all the things that Wallen Pond had to offer. Well, I did leave in 1847. I said, I left for as good a reason as I went there.

It had seemed to me I had now come to the point that I had several more lives to live. That man needs culture too. Of course, after leaving Wallen, I got involved with thinking about social conventions.

I wrote a book called Civil Disopedience because I realized there was a time when laws and social conventions could be so bad, so unjust that they had to be disobeyed because there was a higher law that overruled them. But I wrote, it had all of your rebellion and disobedience had to be done peaceably. And you had to be willing to pay the price for taking on the law.

In fact, I spent a night in jail because I had refused to pay the local tax because I said, part of this tax is going to fund a Mexican war and also keep slaves enslaved. And I couldn't believe that my money should be used to further that unjust law. It was said, and I think it maybe didn't actually take place because I don't quite remember this.

But when I was in jail, Emerson came to visit and he said, Henry, what in the world are you doing there? And it was said, I responded, Emerson, what are you doing out there? I don't think this took place. I don't remember it. But it did catch a truth of how I felt.

And I do know, no, I don't know, but history has said that Mahat Gandhi and Martin Luther King were all influenced by my writings on civil disobedience. And it inspired them in their own work. But all that is another life, another chapter.

Let me just return to what did I learn being at Walden. Many of the people considered me strange anyway and wondered why I would go there. But in terms of being strange, even Emerson, who he was my mentor, the one person I respected more than any other one person, he was to say that through sometimes can be overly argumentative, maybe even bordering on being prickly.

When I didn't like hearing that, I don't consider myself prickly. But I can understand the way I approach life. I can be argumentative.

I remember one time Emerson had just made a plain statement. He wasn't trying to enter a debate. He just said, he was praising Harvard.

And he said, Harvard studies every branch of knowledge. And he left it at that. Well, I thought that was too shallow.

And I said, but not the roots. And it just seemed, this was part of my personality to want to go deeper and dig deeper at every opportunity. And so it made me think about my differences.

And I wrote, if a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it's because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music with his ears, however measured or far away. There's everyone needs to be free to question authority, question the things that are handed down to find out for yourself whether these things are true that are being passed on, because that's only when they are really your knowledge.

Another thing I found that I felt strongly about this. I came through the conclusion that I cannot preserve my health nor my spirits, unless I spend at least four hours a day sauntering in woods, hills, fields free absolutely from all worldly engagements. I found that when my legs moved, that was when my thoughts came.

I also found that nature is so important. If I cut a tree, I could no longer commune with it. I found, oh, I made an acquaintance with Professor Agassi.

And he asked me to send any rare species to him. And so I remember killing the odd snake that looked different, to send to him so he could determine the species. And I began to think just to determine what species the snake's life was taken, as if it meant nothing to anything, it meant nothing to itself.

And I began to think about my own fishing. I loved the fish, but then I began to think and feel, I sort of regret that I took their lives. One person who was actually being a bit ridiculing me as I walked by, he shouted it out, Henry, why won't you shoot a bird so you can study it? And I responded, if I wanted to study you, should I shoot you? But I was coming to this non-conventional thinking that all of life, not just human life, was important and that what you need to do… .