Reverie Nature Podcast

Delve into a diverse array of topics, including wilderness survival skills, bushcraft, nature soundscapes, captivating stories of environmental heroes, secrets in animal tracks, and much more. Ideal for outdoor enthusiasts seeking to enhance their skills or seasoned guides collecting little gems of insight.

Donation or subscription: Buy me a coffee

Hosted in the heart of a land trust site and hiking trailhead: Blueberry Mountain (cliffLAND)

Reverie Nature Podcast

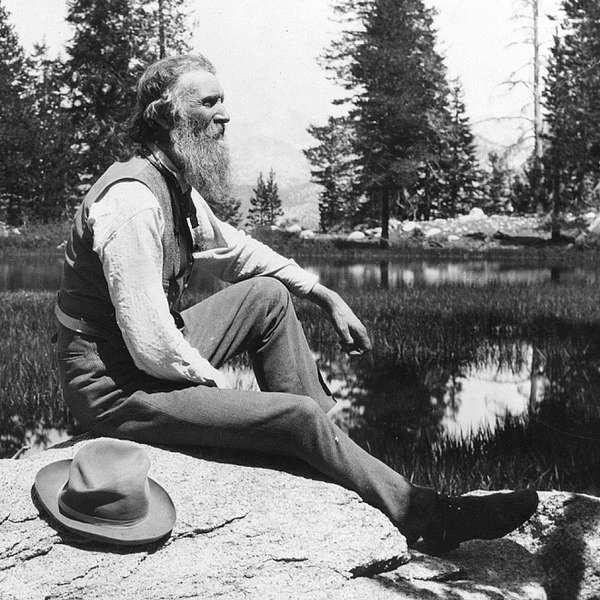

Echoes of Conservation: John Muir's presidential rendezvous

Please support the podcast through a donation or subscription at

Buy me a coffee

The inaugural episode of the Revery Nature Podcast, titled "Echoes of Conservation: John Muir's Presidential Rendezvous," host Chad Clifford delves into the profound influence of legendary conservationist John Muir, particularly focusing on his interactions with two U.S. presidents amid the backdrop of the majestic Yosemite National Park. Muir's (re-enacted by Howard Clifford) pivotal role in advocating for the preservation of natural wonders like Yosemite Valley is highlighted, emphasizing his tireless efforts to protect these sacred landscapes from exploitation and destruction. Through captivating storytelling and reenactments, listeners are transported to pivotal moments in Muir's life, experiencing his deep connection with nature and his unwavering commitment to environmental stewardship. Join Chad Clifford on this special journey through history and wilderness, celebrating Earth Day and honouring the enduring legacy of John Muir and the champions of conservation.

Please consider leaving a rating and/or review wherever you listen to the podcast. Don't forget to share a good episode on social media too. The mid-roll ad on this podcast includes the song entitled House of Mirrors, by Chad Clifford (Pete Meyer on flute).

Thank you for tuning in to the Reverie Nature Podcast! Your support keeps our adventures alive. Be certain to subscribe for more captivating episodes exploring the wonders of the natural world. Join us on this journey to embrace nature's song and preserve the beauty of our planet. Together, we can make a difference.

Chad Clifford

Please support the podcast through a donation or subscription at:

Buy me a coffee

Echoes of Conservation, John Muir's presidential rendezvous

From series: Legends of Environmental Stewardship

The inaugural episode of the Revery Nature Podcast, titled "Echoes of Conservation: John Muir's Presidential Rendezvous," host Chad Clifford delves into the profound influence of legendary conservationist John Muir, particularly focusing on his interactions with two U.S. presidents amid the backdrop of the majestic Yosemite National Park. Muir's pivotal role in advocating for the preservation of natural wonders like Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove is highlighted, emphasizing his tireless efforts to protect these sacred landscapes from exploitation and destruction. Through captivating storytelling and reenactments, listeners are transported to pivotal moments in Muir's life, experiencing his deep connection with nature and his unwavering commitment to environmental stewardship. Join Chad Clifford on this special journey through history and wilderness, celebrating Earth Day and honouring the enduring legacy of John Muir and the champions of conservation.

Transcribed by TurboScribe.ai.

Welcome to the Revery Nature Podcast. Get ready to explore a series of episodes on the Nature Experience, from engaging bushcraft, reading animal tracks and sign, exploring the world of nature, soundscapes and much more. But before we dig in, a big thank you to our listeners.

Please take this moment to subscribe and offer your support to the podcast. I'm Chad Clifford, your host and today's episode officially kicks off the launch of the Revery Nature Podcast, and just in time for Earth Day 2. This episode is entitled Echoes of Conservation, John Muir's presidential rendezvous, where we will listen to an reenactment of John Muir describing his life at a time when he was perhaps at his greatest influence in modern conservation. It's part of an ongoing series I have entitled Legends of Environmental Stewardship.

With Earth Day coming up, how can we not think of John Muir a true champion of conservation? His story resonates deeply, especially considering his unique role when he joined two U.S. presidents on multi-day outings to discuss conservation issues that resonate with us today. In this episode, we're diving into the heart of Muir's interactions with these presidents, recreating those moments to give us a feel for the passion and significance behind them. But why go to the effort of reenacting these moments? Well, to me it's about more than just recounting stories, it's about connecting, connecting with these incredible individuals on a personal level through storytelling.

By immersing ourselves and their experiences, we gain that profound understanding of their dedication, their drive, and their vision, which in turn inspires us to continue their legacy of stewardship for the planet. So get ready to join me on this special journey. Today I'm thrilled to have Howard Clifford stepping into the role of John Muir.

So together, let's celebrate Earth Day and pay tribute to all those who share deep love and commitment to protecting our precious natural world. Yes, it's true that one of the highlights of my many highlights in my life was to have two presidents of the United States spend multi-days with me to consult with me about the important issue of conserving the National Yosemite Park. For those who don't know me, perhaps I'll just give a very thumbnail sketch of my background that led me up to this opportunity to have these visits with the two presidents.

I was born in Dunbar, Scotland in 1838. Perhaps the highlight of my childhood that changed my life would have been in 1849, 11 years of age. My father came into the house, looked at me and my younger brother who were doing homework and said, boys, you'll have no more need of these.

For tomorrow we sail to America. I couldn't believe my years. I mean, I'd read and heard so much about America and to believe that I, with my family, would be going there.

We headed off to America, but I must say my grandfather was supervising our homework and he was obviously sad because we would be leaving. And he said, yes, it might be a wonderful adventure, but it will be some hardships as well. And that certainly turned out to be true.

We arrived in America, went and got a farm near the farmstead near Madison, Wisconsin. And it was through I was the oldest son and had to work from early morning to dusk hard work. But yet the surrounding wilderness, the wildlife, it just thrilled me so different than anything I had seen in Dunbar, Scotland.

Perhaps as I look back at it now, two things came together that was to change the direction of my life. First I had a neighbor who knew I loved books and he would drop books off for me to read. Now, my father, he wasn't pleased about this because he thought books were too worldly.

The only thing that mattered to him, he said, was to know, read and study the Bible. But I guess he felt that he couldn't say I couldn't read these books because he knew that would create tension between us. So he said, all right, if you have a mind to read these books, but remember, you cannot read them between the early morning and when work ends at dusk.

And you must also participate in our scripture readings at night. He knew that by that time all of us would be so dead tired that I would have no energy left to read. But what he didn't know was I've never needed more than four hours of sleep in my life.

And he got around this when winter came. He said, you're not able to start a fire that early in the morning to waste firewood. So I had to go down into the basement, which was a bit warmer.

And they're the second thing that changed my life took place because it turned out I seemed to have an unusual ability as an inventive mind. And so in the basement, I created a mechanical bed with cogs and wheels that I could set for any time. And when it was to go off, it started to raise the bed to a standing position.

And on the way, it had a match to light a lantern, all ready to go, nothing to get ready. This is start reading. And so I spent two to three hours before day break reading these books.

And then a neighbor when I was now in it was now 1860. So I was 22 years of age, came to me and said, John, there's a fair at Madison. Madison, Wisconsin, you should go there with your inventions.

You may find somebody there that would be interested in them or maybe want to hire you. So I took among the inventions that I had created this mechanical bed. And it just so happened that at the fair with Jeanne Carr, the wife of a professor at the university.

And she had her young son and the son of another professor. And they became so entranced with my rising bed that they became my people, the kids that I turned to to use it as an example. And they certainly enjoyed themselves.

And Jeanne Carr was so impressed with my inventiveness and talking with me that he introduced me to her husband, who introduced me to the president of the university. And after an interview, the greatest thing I never dreamed of, he said he would be willing for me to enroll in the university to take any course that I wanted. And that changed my life.

Jeanne Carr and her husband invited me into the home often. And they knew Emerson, that great philosopher. And they knew Thoreau and they had some of their writings and I was allowed to read them.

Also another thing that took place was a fellow student that I met who loved botany. And he introduced me to plants and I just fell in love with them. And so in 1864, leaving university, people thought, well, I should get myself a job and settle down like anyone else would.

But I wasn't ready to do this. And so I entered into what I called enrolled into the great University of Wilderness. I headed to Canada.

Now you have to remember, Canada wasn't even a dominion at that point. There was three years later before it would become the dominion of Canada. It was just a series of provinces that were colonies of Britain.

It was very wild. And yet I wouldn't stay on the main roads. I went into the back country studying plants, sometimes up to my hips and swamps.

It was a marvelous two years I spent there. And then in 1866, I returned to the States during the Annapolis. And I got a job with a leading carriage company, spokes and wheels.

And they hired me and they saw that I had a lot of abilities and they promoted me to become a foreman. Everything was going smoothly. In fact, I began to think, you know, I could prosper here and have a great life.

But one night, working late, I tried to unjam a belt with a file and the file flew up and hit me in the eye. And that I immediately went blind. And by the time I got home, the other eye had gone blind as well.

Total blindness. This was the most depressing time in my life. I was thinking, my God, never to be able to see the beauties of nature again.

But friends brought a doctor and the doctor said, he thought that one eye would recover because it was this sympathetic shock. And the other eye, he said, may have some sight returned, but at least you'll be able to see a game. And sure enough, after weeks of recovery, my eyesight returned.

I had made a promise to myself that if my eyesight returned, I was going to turn my back on this job and study from then on devote my life to studying the beauties of nature, those temples that were made without the hand of man. And so in 1867, I started my thousand mile walk. To follow in the footsteps of Alexander von Bolt, who was my adolescent hero, the one that had traveled to the Andes, the Amazon, and I was going to go in his footsteps.

Now this was just after the Civil War. And by the time I got into the south and specially into Florida, it was a very rough time. There were bandits, there's unrest, so many problems.

My life became endangered on a couple of occasions, but I loved it. Each zone I went into had new plants, new diversity. It just staggered my mind at the beauties of nature.

And then I got to Cedar Keys, Florida. And I took a job just to tide me over at a sawmill, waiting for a boat to take me to Cuba and then make my way on to the Andes. But unfortunately, returning from cutting some wood, I became dizzy and I rented.

They carried me into a bed. It turned out I had malaria. They actually thought they would lose me.

But after a while, I felt I had regained some of my strength. And I embarked on this boat that took me to Cuba. But I found I couldn't even climb the mountains there, I just didn't have the strength.

This trip would just have to be cancelled. And so I headed back on another boat to New York, but I had made friends with the captain. And by the time I got to New York, I felt my strength had fairly well returned.

And he said, would you like to accompany me to San Francisco? Why I'd heard about California and all the tall stories about how beautiful it was. And I thought, well, next to the Andes, this would be my second best choice. And so I went with him.

And I arrived in 1868 to San Francisco. And I asked one of the first people that I thought knew the area, where should I go to get out of town? And the person said, well, where do you want to go? And I said, to the wildest, most leakiest place that you have to offer. And he pointed me to the high sea areas, towards Yosemite.

Or I wish you could have seen California then. I came to a valley about five miles across, and all you could see was flowers and bloom. The most beautiful sight no painter could capture it.

But then, when I came to Yosemite, it took my breath away. I couldn't think of anything that I could add or subtract to make it more perfect. Can you imagine, waterfalls over 2,000 feet high, tumbling over steep cliffs, granite, into a lush valley, a meandering, beautiful river? I mean, it was just a scene out of my imagination that was surpassing anything that I could imagine.

And for some reason, I knew this was to be my home, which I took on odd jobs. Every moment I had, I ventured out, exploring, looking and observing, everything I could see. And I'm sure I wouldn't be exaggerating to say that I came to know this area probably better than any other man in history.

And during that time, I met so many wonderful people, scientists like Asa Gray, the great botanist. I took him on tours with other botanists, and I even sent him plants that I found that he may be interested in. In fact, he named.

And one of the things that I really turned my mind to was how this wonderful valley was formed. I had read that Professor Whitney had said that the bottom had simply fallen out at creating the valley. But I knew, for my observations, this couldn't be true.

It seemed to me every observation I made, that it was by the action of glaciers. While he certainly criticized these views, saying, what does this sheepherder know? Because I had already written that I had spent a summer looking after somebody's sheep. But I didn't back down because I knew what my eyes saw.

And pretty soon, there were a couple of other scientists that began to think there might be something in my view. But probably what brought it to a head was when Professor Lewis Agassay, the most eminent person in the world, on glaciation. And though I didn't meet him, he read my writings.

And his wife said that he told her that this was the first man who has an adequate understanding of glaciers. And of course, today, most scientists say that my view was most correctly capturing what had taken place. And also, I became friends with some of the industrial tycoons.

One invited me, along with John Burrows and others, on an expedition to Alaska. And part of my duties was to examine the glaciers. These were wonderful trips.

And I, during this period, wrote a few articles and became somewhat known, somewhat nationally known. And then in 1889, Robert Underwood Johnson, he was the editor of the Century magazine, one of the most influential magazines of the day. And he had also heard the greater area of the Osenome, was underseized, that it was being destroyed by lumbering and by overgrazing by sheep.

And he wanted to see it for himself. So he contacted me, asked me to accompany him to the Osenome. And as we walked in the area, he saw for himself firsthand the things that I had been talking about, the dangers of losing this beautiful, beautiful scenic area.

And over a campfire, he had a suggestion. He said, John, I want you to do two things, to write two articles. The first will be entitled, The Treasures of the Osenome.

And then it will be followed up by your second article, a proposal to make it a national park. Well, I was thunderstruck thinking this will be futile. How could we possibly, when all these people would never want to turn all this land to a national park? But I couldn't say no.

And so I wrote the two articles, and he made them broadly available to most influential people. And we couldn't believe what we saw, 1890, the Osenome, a national park. I couldn't believe that we had accomplished this.

Well, you see, the Osenome Valley and the Maripros of Grove had been given by President Lincoln to the state of California to be used for the benefit of people. But all this other area surrounding it, the larger area, was now a national park. In fact, just two years after that, I was a co-founder of the Sierra Club of America.

And I think you know how influential that club became. And then in 1903, President Teddy Roosevelt made it known that he was doing a Western tour, and he wanted the tour of the Osenome, and he wanted me to guide him. But I didn't want to do this.

I had already made or already accepted an invitation from Charles Sargent, who was the America's best person on force, and he wanted to have me go with him on a world trip to Siberia China, to study the trees and the forests. And this was the love of my life. I mean, this is what I dreamed of doing.

So I wasn't about to simply accompany a politician on a political tour. He must have heard that I was considering not being there because I got a letter from him, a personal letter. And in it he throat, I do not want anyone with me but you.

And I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you. Well, how can I turn this down? I mean, the Osenome, and especially the Osenome Valley and the Mariposa Grove, would still be misused, even though it was under the control of California. And so even Charles thought, no, he was disappointed, that I understood I had to go with the President.

And he gave me a letter, sent me a letter saying, well, make sure you ask the President to phone Russia and China to get us permission to visit some of these places that they may be reluctant to let us see. Well, May 15th, 2003, Roosevelt arrives. And true to his word, he dismissed the secret service and just had two rangers.

And there we were underneath the grisly sequoia, that most beautiful grove that you can imagine. And I was surprised that the packed person laid down 40 blankets for the President to sleep in. I think he must have been equally amazed to see me pull out a piece of cloth, really, wool cloth made up bed of bows and the cloth would just to wrap around myself.

There's something about that grove, there's a majesty. It was there before Christ was born, these magnificent trays, what a temple. And at night, what a hush comes over the grove.

It's almost like these giants were giving their patriarchal blessing. My mind actually turned to Emerson. I had mentioned previously in the letter to the President how disappointed I was when Emerson, who I think was the greatest person I've ever met, came to visit your enemy.

And I had talked them into as they were going to be leaving to go back to San Francisco to spend a night with me at the Miraposa Grove and he agreed. When we arrived there and was having lunch, I noticed no one was putting up a camp. So I said, aren't you staying for the night? And the people around him said, oh no, he's too old to camp out there, it's too cold.

We can't have him catch a cold. He's got business to do in San Francisco. And Emerson looked at me with sad eyes, showed his shoulders and said, I'm sorry, John, I won't be able to spend the night.

I followed him as he walked among the trees and he didn't know I was behind him. But I heard him say to himself, quoting scripture, in those days there were giants upon the land. And when they got on their horses and rode off, he shriveled in his saddle, turned to face me and waved goodbye.

I felt so desolate, I had so much wanted to share this experience with him. As I said to me, he was the greatest person I've ever met, he's the only person I ever said this about, that when I looked into his eyes, I saw the soul of a sequarietary. No greater compliment could be paid to anyone.

When I spent the night there and I was nourished, my spirits rekindled by these gentle giants. And I knew Teddy Roosevelt was captured by these giants as well. You could tell in the tone of his voice the type of conversation that took place.

The next day we were alone, we went to the sentinel dome, what a beautiful duck out. Everything you saw for miles was majestic, I let nature do its thing. Oh I like to talk a lot, and I did talk a lot.

And of course Teddy Roosevelt is known as a talker. And it amazes me yet that we got along so well, for we not only each talked, but we both listened. We both thought each had something important to say.

Well I remember one thing I said that I sometimes wonder if I should have said it. He was going on and on about all the hunting trips he had been on. The trophy antlers, I couldn't help myself.

I simply turned to him and said, Mr. President, when are you going to put these childish things away? You know that these are beautiful animals. Why do you simply want to take the best and take the lives away? Well he turned, he looked aghast, no one had spoken to him like this.

Transcribed by TurboScribe.ai.

And then he passed and said, perhaps you have a point. I remember my friends later when I related this story. Then how could you have done that? I mean, you had the president there and to offend him, when you were wanting him to save this place, how could you have done it? But the president later relating this experience was to say, John was a man who never wanted to give offense and never felt anyone should take offense by what he was saying.

He was a person without guile. Well, the next morning I thought maybe everything had been lost. I woke up and there I saw the president lying under five inches of snow.

I mean, that might dampen the average person's appreciation of being out in the wilds. But in moments he arose, stood up, shook the snow off his blanket, and he said, Bully, isn't this the best day of our life? And I knew right then that he was a true lover of wilderness. Oh, I know that he loved the mantle of being seen as a rugged cowboy, an outdoorsman, a hunter, even cherished the image of him, riding a horse as a military leader, leading the charge in Cuba up a hill.

But I never believed that I would hear the kind of utterances that he made while in the ost enemy. One of the things he said that really impressed me, he said, there can be nothing more beautiful in the world than the ost enemy. To speak to him, yes, he caught the spirit of the place.

And then when he left, he said, we are not building a country for a day. It is to last through the ages. Somebody wrote an article about this trip called, headed it, the camping trip that changed the world.

In many ways, I think this is true. I know my heart sang when Congress transferred the ost enemy valley and the Mariposa Grove from the care of the California State government to the national government. It became a part of the national ost enemy park.

This was accomplished, not because of any naturalist or anything that I might have said or wrote. What made it happen was when a person experiences the beauty and majesty of this area themselves, it hits you emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually. It was nature working its way, its magic upon him.

He went on to have created five national parks, 18 national monuments, 55 national bird sanctuaries, and 150 national forests. No president has ever saved so much land. Can you imagine what America would be like if these areas that he saved had been destroyed by the greed and desecration of man? Well, in 1909, President William Taft, who had been selected by Roosevelt himself to be his successor, contacted me and said he wished that I would take him on a tour of your enemy.

Now, you have to remember, this was doing the battle of my life because some greedy people from San Francisco had their eyes on the het het she. That was part of the Housenami National Park. In my mind, it was a twin jewel of the Academy Valley itself, and they wanted to flood it to create a dam so they could get water for San Francisco.

It was a six-year-long fight of my life. At one moment, we thought we were winning the fight. Next moment, we thought we were losing it.

And by the time I was contacted by President Taft, it had already been cited that the go-ahead had been given that it would be damned. It seemed we had lost the battle. I couldn't have turned down his request to show him the Academy.

He simply said he just wanted to see what the fuss was all about for himself. And when he arrived, it started out, what I would say, kind of poorly. The plan was to go by horseback to the Mariposa Grove.

But the horse they brought was too small for this president. I mean, he weighed about 330 pounds. We went by stagecoats to the Mariposa Grove.

And we stood before that same grisly sequoia that Teddy Roosevelt and I had leapt under. And he, too, was taken by the majesty of this Grove. You could see it in his appearance, his quiet observations.

And then we went to the Glacier Point, that beautiful spot. And the president said he wanted to walk down, about a four-mile walk to the valley. I wondered about the wisdom of this.

I mean, here he was, over 300 pounds. It wasn't the easiest trail down. I turned out he was the merriest man I had ever met.

He never complained at all about the walk down. He took in everything. He certainly had a sense of humor.

At one point, we came to this beautiful part in the river. And he said, John, wouldn't this be a wonderful place to make a dam? He knew exactly the reaction I would give. I said, yes, Mr. President, but anyone who dammed this would be damming themselves.

And he burst out in laughter. When we got down to the valley, he said, while I am tired from the open-air exercise, I feel generally better for it. Right then, my own opinion was affirmed.

That wilderness like this can refresh, benefit all people. In fact, I was 71 years of AIDS myself during this time, but I was in extremely good shape. He asked me if then I would take his secretary of the interior, Richard Ballinger, take him to see the het het she himself because it was too far a distance for the President to make.

I agreed. And it turned out that Ballinger wasn't going to see it just because the boss had asked him to. He had a genuine interest, and he too was captured by the power and beauty of this place.

I couldn't believe it. When the next thing that happened was that he ordered San Francisco to show cause why the het het shet shouldn't be deleted from the plan. At night, we had won.

Everybody thought now our fortunes had been reversed. We had won. Het het she would be saved in 1911.

I knew my health was failing. I had actually said to my daughter, this het het fight valley, fight has to end. It's draining my life forces from me.

I can't continue much longer. And so in 1911, I had the last opportunity. I had to take it to go to the Andes.

I was 73 years of age, and I fulfilled this lifelong dream. It was wonderful. Then, when I got back, something tragic had taken place.

Secretary Ballinger and Pinchot had got into a conflict. Pinchot had already, even though we had been great friends, I couldn't believe he had turned his opinion on behalf of building the dam. I don't know the details of the conflict.

But it resulted in Teddy Roosevelt feeling that Tapp was retraining the reform aspects that he had promised to keep. Though Tapp himself and I believe him said no, he had every intention of continuing the reforms that Roosevelt had started. But Roosevelt, he couldn't run for President of the Republicans because that nomination had already taken place.

So he started a third party. And between Tapp and Roosevelt, they split the vote. And President Wilson, with only 42% of the vote, won.

And very soon after, he appointed to be his Secretary of the State, Franklin Lane, who had been a promoter of the dam. And in December, 1913, Congress passed the bill allowing Het Hetchy to be flooded. I was devastated, of course.

I had never spoke publicly than I recall about the Ballinger and Pinchot debate or conflict. I knew it had something to do with Ballinger giving some public land to a person in Alaska for the development of coal. And it's quite likely I might have been on the side of Pinchot on that one.

But that decision that he made pales so much into insignificance compared to what Pinchot allowing the dam to be built. I mean, this was more than just a decision about a dam. This was an existential problem.

I mean, I had once said that these forests, these groves, been here before Christ was born. That God had protected them from floods, from storms, from droughts. But he could not protect them from fools who would cut them down.

That only Uncle Sam could do that. And when the obscenemy was made a national park under the protection of the power of the national government of the United States, if that could be undermined, then what hope do we have that anything could be forever protected? Pinchot, he had a very catchy saying. He said, when decisions like this come to be, you don't look at the scenery, you don't look at the wildlife, you look for the greatest good for the greatest number.

Now that seems very democratic on its surface, but it's so shallow. I remember doing my, my position is clear, even though I didn't speak to him about this. In my thousand-mile walk, when I saw the variety of species, but I hadn't seen before, plant species, wildlife, I wrote.

You know, it has never occurred to many of the leading minds that all of this creation may have been created for the happiness of each and every one of these species. Many of these species hear eons of time before man arrived on the scene. Why would anyone suppose that all of this creation was made for the happiness of one species, Lord Man, it makes no other sense when he speaks about the greatest good of all? Who is he talking about? Was he talking about the pockets that were lined with silver in San Francisco, because they could take this treasure out of this national park? Were they speaking for the voices of the plant people, for the wildlife in this area that were supposed to be protected forever? The one thing I did say at this time was some sort of compensation must truly come out of this damned damn damn nation.

My word proved to be true. For just two years later, with two years after my death, the Congress of the United States created the National Park Service Mission. This was directly a result of all the people who rebelled, who were so upset with the decision that the government had taken to create this damn.

And in the mission of this act, it said to conserve the scenery and the historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same, in such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations. But like Roosevelt, like Tath, like Ballinger, they had to come to see for themselves to let them magic the power of nature touch their souls. To reach them emotionally at their depth, for nature is the best teacher.

All the books in the world is not worth anything compared to your genuine experiences with nature. I have done the best I could to show forth the beauty, grander, and all embracing usefulness of our wild mountain forest reservations and parks. With the view to inciting the people to come and enjoy them, get into their hearts.

That's so at length, their preservation and right use might be made sure. I say to future generations, I know the plight will continue. I mean, we won the creation of your enemy.

We won the battle to have California turn your enemy valley over to the park. We won many battles. But the fight always continued.

There was always this sense of greed that no matter the beauty, no matter the importance, if there was a but to be made, there will be people of power, of vested interest, who will strive to undo all the good works that we've done. And so I invite you to join the people who know in their hearts that we're part of nature, that we need nature, and that Lord man cannot prevail. It's not the only voice of creation.

It's sure that if man disappeared, nature would lose. But just as true, any other species that disappear, nature will lose. Yes, we need nature and the things that nature can produce.

But we also need these sacred places that speak to our souls. Beauty. I mean, without this, what will we have? So support conservation groups, land trusts, have your children visit, get it into their souls, so they'll know what they're fighting for.

And not simply have amnesia because they never knew what you and I have seen. So yes, the visits by two presidents of the United States was a great honor to our naturalists. We need to continue the fight.

Thank you. Thank you for joining us on the Revery Nature Podcast. Remember to subscribe for more captivating episodes exploring the wonders of the natural world.

Until next time, may you saunter forth embracing nature's song and be the whispers of the wilderness linger in your heart.

Transcribed by TurboScribe.ai.