Reverie Nature Podcast

Delve into a diverse array of topics, including wilderness survival skills, bushcraft, nature soundscapes, captivating stories of environmental heroes, secrets in animal tracks, and much more. Ideal for outdoor enthusiasts seeking to enhance their skills or seasoned guides collecting little gems of insight.

Donation or subscription: Buy me a coffee

Hosted in the heart of a land trust site and hiking trailhead: Blueberry Mountain (cliffLAND)

Reverie Nature Podcast

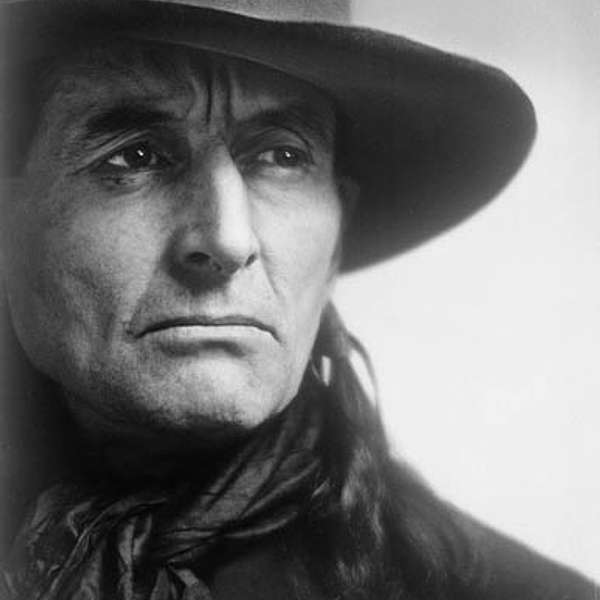

Champion of the Wilderness: A Journey with Grey Owl

Please support the podcast through a donation or subscription at

Buy me a coffee

We delve into captivating stories of environmental stewardship. In our new series, "Legends of Environmental Stewardship," we explore the lives of visionary figures who shaped conservation history. Today, we embark on an inspiring journey with Grey Owl, a complex and enigmatic figure whose life journey traversed continents and cultures, leaving an indelible mark on the conservation movement.

Grey Owl, born Archie Belaney in 1888 in Hastings, England, later adopted an Indigenous identity, dedicating himself to the protection of wilderness and wildlife in Canada. Through his compelling writings, captivating lectures, and magnetic persona, Grey Owl captured the hearts and minds of audiences worldwide, shedding light on the challenges facing North America's forests and wildlife.

Picture yourself by a tranquil lake near Tamagami, as storyteller Howard Clifford unveils Grey Owl's profound connection to nature and his enduring legacy as a champion of the wilderness.

Archie's upbringing was marked by hardship and a longing for freedom. Raised by two maiden aunts, he yearned for the vast wilderness depicted in his childhood fantasies of Native American life. At 17, he ventured to Canada, seeking the freedom he dreamed of.

In Canada, Archie found solace and belonging among Indigenous communities, eventually marrying a full-blooded Indian woman named Anahiro. Together, they forged a deep connection with nature, living off the land and developing a profound understanding of its inhabitants.

Archie's encounters with wildlife, particularly beavers, transformed his perspective on conservation. Witnessing their plight at the hands of indiscriminate trapping, Archie became their staunch advocate, devoting his life to their protection.

His efforts gained recognition, leading to a pivotal role as the first naturalist in Prince Albert National Park. Through speaking engagements and publications, Archie raised awareness about the importance of conservation, captivating audiences across continents.

Archie's journey culminated in a remarkable moment at Buckingham Palace, where he shared his message of conservation with royalty. His unwavering commitment to wildlife and wilderness preservation left an enduring legacy, inspiring generations to cherish and protect our natural world.

Join us as we celebrate the life and legacy of Grey Owl, a true champion of the wilderness.

Don't miss out on future episodes of the Reverie Nature Podcast. Subscribe now and join us on this captivating journey through the world of environmental stewardship.

Please consider leaving a rating and/or review wherever you listen to the podcast. Don't forget to share a good episode on social media too. The mid-roll ad on this podcast includes the song entitled House of Mirrors, by Chad Clifford (Pete Meyer on flute).

Thank you for tuning in to the Reverie Nature Podcast! Your support keeps our adventures alive. Be certain to subscribe for more captivating episodes exploring the wonders of the natural world. Join us on this journey to embrace nature's song and preserve the beauty of our planet. Together, we can make a difference.

Chad Clifford

Please support the podcast through a donation or subscription at:

Buy me a coffee

Transcribed by TurboScribe.ai.

(0:00 - 0:22)

Welcome to the Reverie Nature Podcast. Get ready to explore a series of episodes on the nature experience from engaging bushcraft, reading animal tracks and sign, exploring the world of nature soundscapes and much more. But before we dig in, a big thank you to our listeners.

(0:22 - 0:43)

Please take this moment to subscribe and offer your support to the podcast. I'm Chad Clifford, your host and guide, and today I'm introducing a new series on the Reverie Nature Podcast. It is called Legends of Environmental Stewardship.

(0:45 - 1:03)

So as we embark on this captivating journey through time, we'll breathe life into the stories of visionary figures who shape the course of environmental conservation. People like John Muir, David Thoreau and Grey Owl and more to follow. Let their stories inspire and ignite your passion for nature and environmental stewardship.

(1:04 - 1:20)

This episode is entitled Champion of the Wilderness, A Journey with Grey Owl. In the realm of conservation, Grey Owl stands out as a figure of both complexity and mystery. His life journey traversed continents and cultures, leaving an indelible mark on the history of conservation.

(1:20 - 1:58)

Born Archie Belaney in Hastings, England in 1888, Grey Owl would later adopt an indigenous identity, dedicating himself to the protection of wilderness and wildlife in Canada. Through his compelling writings, captivating lectures and magnetic persona, Grey Owl captured the hearts and minds of his audiences worldwide, shining a light on the challenges that faced North America's forests and wildlife. Now picture yourself by a tranquil lake near Tamagami, with a gentle breeze blowing off the lake as storyteller Howard Clifford reveals Grey Owl's profound connection to nature and his enduring legacy as a champion of the wilderness.

(2:01 - 2:22)

My name is Archie Belaney, better known by most as Grey Owl. I was born in 1888 in Hastings, England. My father had a serious drinking problem, and my mother was only 14 years of age.

(2:23 - 2:48)

And so the total family thought they just were not capable of taking care of me. And so the decision was made for me to be raised by two maiden aunts. Now, you have to remember, back in those days, it was a real problem, a stigma.

(2:49 - 3:35)

If you had a father who was alive but wasn't there to look after you, and there was only one other child in my school that was in that situation, and none that had neither a father or a mother were both alive that were not in the home. And my aunt, both of them, but one that did the most in raising me, she did her best, she did care. But I think she always worried that I might have the kind of family background of my father and mother.

(3:36 - 3:55)

And so she was very strict. And when I tried to find out information above my parents, I could tell she just didn't want to talk about them. And it was almost as if she felt that they were inferior, and that made me feel, well, I inherit their genes.

(3:57 - 4:38)

Maybe I am too. But during my childhood, I tried to escape by, oh, I'd read books about Indians in the United States and Canada. And I thought, oh, wouldn't I love to be born an Indian? Just think, get up when you want to, do whatever you do, perfect freedom, and a land where rivers would go for hundreds and maybe even thousands of miles, forests so vast, they could swallow up my little town of Hastings.

(4:39 - 5:06)

And so all my fantasy was being Indian. Where others would play cowboys and Indians, I was always the Indian. And when Buffalo Bill actually came with his Indians to ride cowboys to our town, everybody else, of course, wanted to see the cowboys, but me, I wanted to see the Indians.

(5:08 - 5:26)

And so I was a bit of a rebel. And when I was 17 years of age, I'd finally convinced my maiden aunt to let me go to Canada. And so I was only 17, it was 1906.

(5:28 - 5:55)

And I got a job in Toronto in Eaton's, but, you know, there was no Indians there. So I saved up as much as I could until I had enough to take a train to go where people said the Indians were closest, and that was Tamagami. But they warned me, they said, you're white, they're not going to want to have anything to do with you.

(5:56 - 6:13)

And as they got closer to Tamagami, I began to have this little fear that maybe I had fantasized too much about them. Maybe they wouldn't want to have anything to do with me. But, oh, they took me under their wing.

(6:15 - 6:41)

I think the difference is that they know your heart. And when they are mainly related to white people who thought they were inferior, they're not going to be giving themselves to them or sharing their inner thoughts. But with me, they knew how much I respected everything that they stood for and that I wanted to be like them.

(6:43 - 7:09)

Well, I was only 22 when I married a full-blooded Indian woman, Angel. And so Angel and I got married, and she knew my heart, that I really wanted to be just like them, identify with them. And she taught me so much.

(7:09 - 7:30)

How to speak Indian. But I'd go hunting with the other Indians, and sometimes we'd go for quite a few weeks at a time. And it got that I was going longer and longer and longer apart.

(7:31 - 7:48)

And it was my fault, nothing that she ever did, but I married just wasn't working out. And I found myself going further and further away. And, oh, I recall this one time.

(7:49 - 8:11)

I went to this place where I was going to set up camp, build a cabin while the cabin was already built for the winter and to spend the winter there. But it was one of those beautiful late fall days. And so I thought I would just go and scout around.

(8:12 - 8:36)

There was a bit of snow on the ground, but it was so warm that I didn't take any warm clothes or anything because I was only going to go for a couple of hours just to see where it might be best to put my traps and so forth. But as it was getting dark, all of a sudden we were hit. Well, I was hit by a blizzard.

(8:37 - 8:55)

I couldn't even see six inches in front of my eyes. And so I kept going and going, and I realized, oh, I'm lost. But then suddenly in front of me I saw snowshoe tracks.

(8:55 - 9:12)

I thought, oh, there must be another trap around here that I hadn't heard about. Certainly I'll follow these tracks, get to his cabin, and they'll certainly make me welcome. And I went and I went, and then I noticed there were more snowshoe tracks.

(9:13 - 9:26)

And then went and went, and it was even more. I thought, there must be an Indian group up here. And then a sudden thought hit me, and I looked at my snowshoes and they were the same.

(9:26 - 9:46)

I'd been walking all this time in circles, and I had no idea where I was. But on this one little ledge, they broke just for a minute where I could see, and I saw my cabin. And so I made my way back there.

(9:46 - 9:58)

I would have perished for sure because I hadn't any warm clothes. I didn't really have the skills to make it overnight. And so you wouldn't even be hearing about this story.

(9:59 - 10:17)

It hadn't been that the snow storm just broke for that minute where I could then see my way back to the cabin. Well, I eventually made my way to Bisco. Oh, it was a wonderful country up there.

(10:18 - 10:42)

And I got jobs with the ministry and spending my time trapping and making friends with Indians there. And then I went back to Tamagami. I was now 25 or 26 years of age.

(10:42 - 11:30)

And as I was canoeing into this resort area, I noticed this Indian lady watching me. And so I put on my sort of stride to be a real Indian because by this time I had been telling people that I was half Indian and half white that I had a Scottish father and my mother had been an Apache. Well, it turned out that her name was Bernard.

(11:32 - 11:50)

Gertrude was her first name. And I thought, Gertrude, what kind of a name is that for an Indian? Your name is Anna Hero. And from that day on, that's what people called her and what she was known for for the rest of her life.

(11:52 - 12:16)

Well, she was full-blooded Indian from Ottawa town of Manawat. And she did go back, and I went there to visit. And it just turned out that she was a bit of a rebel herself and she had thought of me as Jessie James.

(12:17 - 12:37)

So I talked her into going with me for the winter on a trapping trip. Well, even though she was full-blooded Indian, she was a town Indian. She had never really spent any time out in the woods except maybe the odd overnight thing.

(12:39 - 13:00)

But she put on her pack sack and was following me and we'd gone for a few hours and she said, Archie, how much further do we have to go? I said, oh, not far, 40 miles. She said, 40 miles. But she kept on going and going.

(13:01 - 13:18)

And then we got to this place where I had my friends build a cabin. But she didn't see the cabin. What I had was a root house where you could go down into this cave.

(13:19 - 13:34)

And that's where I said, this is where we're going to be spending our winter. And she went down in there and it was built out, had a little stove and stuff. But she just couldn't believe that this is what she was going to be spending the winter in.

(13:35 - 13:52)

But in the morning came out and there was the cabin. And we called it Pony Cabin because her nickname was also Pony. Well, at first I left her behind as I went trapping.

(13:54 - 14:07)

But she kept saying she wanted to come. She wanted to come with me. So this one day, she was with me, but we were coming to this small lake, mainly a big pond.

(14:08 - 14:23)

But it's dangerous because it's ice, but it could fall through. And so I knew already I had enough experience. I could with my stick just tap the ice and just know how strong it was.

(14:23 - 14:44)

And so I said, you stay back at least 30 feet from me because if the ice is going to break through, you don't want to be near it. Well, I was tapping away, going very cautiously. And all of a sudden I hear this bang crash.

(14:45 - 14:53)

I thought, oh no. I turned around and sure enough she had tried to catch up and she went through the ice. And disappeared.

(14:54 - 15:07)

And I'm trying to get back there, but the cattle go slow because the ice was that rotten. And there she popped up. And I got down on my stomach getting close.

(15:07 - 15:23)

And with my stick, I gave it to her to pull on, to climb out. And then I said, you run back as quick as you can now to the cabin. And I'll get some firewood so we can get a fire going.

(15:23 - 15:34)

But you've got to run fast because your clothes are going to freeze and you'll only be able to move. Well, she managed to get back. I managed to get a fire going.

(15:34 - 16:01)

We got her under all the blankets and she survived. But that was another instance of how people that really don't know what they're doing can get in serious trouble in the Canadian wilderness. We had, of course, numerous adventures and things that brought me more and more into good relationships with the native community.

(16:04 - 16:25)

But because of shortage of time now, I'll just mention that we had to go further and further to do trapping because the beavers were just disappearing. They were just being trapped by a lot of newcomers that were coming in. And they were not good trappers.

(16:25 - 16:42)

And they would actually blow up the lodges with dynamite. And they didn't care like the Indians did. They would never hunt when their kits were there because then you're not going to have any future beaver colonies.

(16:44 - 16:58)

And so we were noticing this. And then one day a white person who was a new trapper as well, but he was a friend, a good-hearted person. And he came to me and he said, Archie, I need help.

(16:59 - 17:18)

I've trapped this beaver, but somehow it didn't work. And it's standing now trapped on top of the lodge. And would you come and shoot it for me? So I certainly didn't want any suffering like that to take place.

(17:19 - 17:36)

So I went and there was this beaver with its one arm caught in a beaver trap. And so I raised my rifle. But just as I took another look, I saw into her eyes a deeper hurt more than the physical pain.

(17:36 - 17:48)

It seemed like almost what you'd call a soul pain. And then I looked more carefully. And in her other paw was a baby kit and she was nursing it.

(17:49 - 18:16)

And it was if her fear and anguish was that this was the last meal she knew she'd be able to give to her kit. And then what would happen to that kit? It would either starve to death or be torn apart by wolves or other predators. And so I dropped my rifle and I knew her arm would be pain-free now because it would be without circulation.

(18:17 - 18:40)

I took my hatchet and I cut the arm off with a paw off and there she was free. And she looked at me as if to say, I know you are the enemy of our people. You kill us for no reason, but somehow you found it in your heart to have mercy on me and my kit.

(18:41 - 19:00)

And then with the kit in her arm, she dove into the pond. Well, that shook me. And then later that fall, I'd actually, well actually now I was in the spring.

(19:02 - 19:10)

And it was too late really. I knew it was too late. But, oh well, I'm going to pick up my traps.

(19:10 - 19:35)

And Anahiro and I was in the canoe and as we were getting close to where the last trap was, we heard like a baby crying in the wilderness. And Anahiro said, would anybody be away out here with a baby? And I said, no, that's a baby beaver. They're crying just like a human cries.

(19:36 - 19:47)

And she said, oh, then we've got to get it. And I said, yes, we do, because I wanted to put it out of its mercy. We were too late in the season that we shouldn't have been trapping then.

(19:49 - 19:59)

And there we heard the cry of the baby and the other one. There's two of them. So I managed to grab one and gave it back to her.

(19:59 - 20:14)

And then I paddled and got the other one. And I noticed she was putting them down her bluffs. And I said, what are you doing? She said, well, I'm taking them home to our cabin because I'm going to raise them.

(20:14 - 20:23)

And I said, what kind of an Indian are you? You can't possibly raise these. Yes, I can. Until they're old enough to go on their own.

(20:24 - 20:40)

Well, I knew she was strong minded. And therefore, I thought, well, it's not going to work out, but so be it. Well, all that summer, they were growing.

(20:41 - 20:58)

And I learned something about them that was different than anything I knew about them before. I knew everything that Beavers did. I knew where they built, why they built, what kind of food they ate, everything about them.

(20:58 - 21:11)

Except I didn't realize this, that each one of them had a distinct personality. Just as each human being has a distinct personality. And both of these little Beavers had different personalities, too.

(21:12 - 21:24)

But they had taken us as if we were their parents. We were part of their family. And when I'd go off hunting, and it'd be gone a few days, they would come back.

(21:25 - 21:37)

And I would come back, rather, and there they were. And they would be so angry at me, thinking I had deserted them. And they would stomp their feet, and one would even come up and point his finger right on my chest.

(21:38 - 21:55)

But soon, it was just hugging and really happy to see me. Then it came time to move camp. And so we had all of our stuff put into the canoe, and went to get the Beavers, and one of them was missing.

(21:56 - 22:14)

So I got in the canoe, going around and around, trying to find them, spent hours looking. And had given up, and had just gotten almost back to the cabin, when I heard its call. And there it was stuck in the muck, back in this eddy.

(22:14 - 22:26)

And it was almost like in quicksand. And I went there, and I couldn't reach it because it was in the muck. So I stepped out of the canoe and grabbed him, but then I was sinking, deeper and deeper.

(22:26 - 22:39)

But by then, Anahiro had heard the rakis, and had come. And so I handed the beaver to her, and then managed to get out. I cleaned myself off of all this muck.

(22:40 - 22:50)

And I was so angry because now we couldn't leave. It was too late in the evening. And I knew if I said something, I would just say many things that I should not be saying.

(22:51 - 23:05)

Because I was so angry. And I cleaned myself off, laid down, exhausted on the bed. And I noticed the little beaver was cleaning himself off, too.

(23:07 - 23:29)

And then just as it about to doze off, the beaver jumped up on the bed, onto my chest, looked me straight in the eye, as if to say, I knew, I know that you were angry with me, but you saved my life. And it began to nestle under my chin. And within 30 seconds, we're snoring away.

(23:30 - 23:52)

And I knew at that point that I loved them. And the next day, I gathered my traps again and threw them on the table and said, down a hill, I am no longer a trapper. And she had tears in her eyes.

(23:52 - 24:06)

She said, oh, how long I wanted you to say this. And I said, but what can I do? I can't go back and live in a city. And she said, no, but you're writing books.

(24:06 - 24:21)

You had articles that had been written. And you speak really, really well. Why don't we use you to do that, to start an organization to save the beaver? You know they're disappearing.

(24:22 - 24:46)

Look what would happen to the Indians and everybody else if Canada lost its beaver population. Well, somehow word got out, and I was invited to speak to this group, and they said they would take up a donation for me. And this is my first public speech.

(24:47 - 25:09)

And I felt like I had just was like a rattlesnake that had swallowed the icicle. I just thought, I can't say anything. What am I going to say? And then I looked in the corner, and there was Anna Hero holding one maginti, which was one of the beavers.

(25:10 - 25:28)

And I knew I was speaking for something much bigger than myself. And so I spoke, I think, probably for an hour. And afterwards, she said, the woman that organized it said, here is the donation we've taken up.

(25:29 - 25:38)

One thousand dollars. That would be more than I would make in two or three years. Well, then it happened.

(25:39 - 26:00)

That word got out to the federal government about looking after these beavers. And so they offered me a job as the first naturalist in Prince Albert National Park. And they had a little lake that was about 20 miles off the main lake.

(26:00 - 26:22)

Just far enough that people that really wanted to talk with me would be able to hike that distance. But the people that would just curiosity seekers, that would be too far for them. And so in this little lake, they built a cabin for us.

(26:23 - 26:50)

And our two little beavers began to build their lodge, and they built it right against the house and actually came into our house and was right underneath us. Well, then we got word because I had written this book. And this person that had become a publisher was actually from England.

(26:52 - 27:10)

And they wanted to promote the book and to have me come there for a couple of months to promote the book. And they set up hundreds of different speaking engagements. And sometimes I'd do two in a day, once in a while even three engagements.

(27:12 - 27:42)

And it was so popular that they kept knitting more and more venues. In fact, they say I spoke to over 250,000 people during that time. And during that time also, the king and the king's mother, the mother had read my book and was thrilled that I was in England and asked the king to invite me to speak at the Buckingham Palace.

(27:43 - 28:05)

Well, just think, they thought I was Indian, or at least half Indian. And yet I hadn't been, I'd been raised not that far away at Hastings. But I went and they said, well, the people around that was organizing it said, okay, here's how it works.

(28:07 - 28:15)

You will be here when the king comes in. He'll come in last. And then he'll stand.

(28:16 - 28:25)

And then when he's seated, he'll speak. And you only speak for 20 minutes. And I said, no.

(28:26 - 28:39)

I said, what do you mean no? I said, no, I'm representing the Indians of Ontario. And I'm representing the Beaver people. I come in last.

(28:41 - 28:58)

And my publisher was there and said, you know, don't disturb things like this. I said, no, it's either that or I don't do it. And so the people that worked for the king went over and whispered something in his ear.

(28:59 - 29:15)

And he smiled and nodded. And so I came in last. The king and family, the princess was only a teenager then, a young teenager.

(29:17 - 29:30)

And say, of course, now is your queen. But I thought, well, they've gone this far for me. I will honor the 20-minute limit on my speaking.

(29:31 - 29:48)

So I spoke for 20 minutes. And then about to stop when the princess Elizabeth yelled out, oh, Mr. Greal, won't you speak some more, some more? And I looked at the king. He smiled and nodded.

(29:49 - 29:59)

So I ended up speaking for an hour. Well, then I came back... .

Go Unlimited at TurboScribe.ai to transcribe files up to 10 hours long.